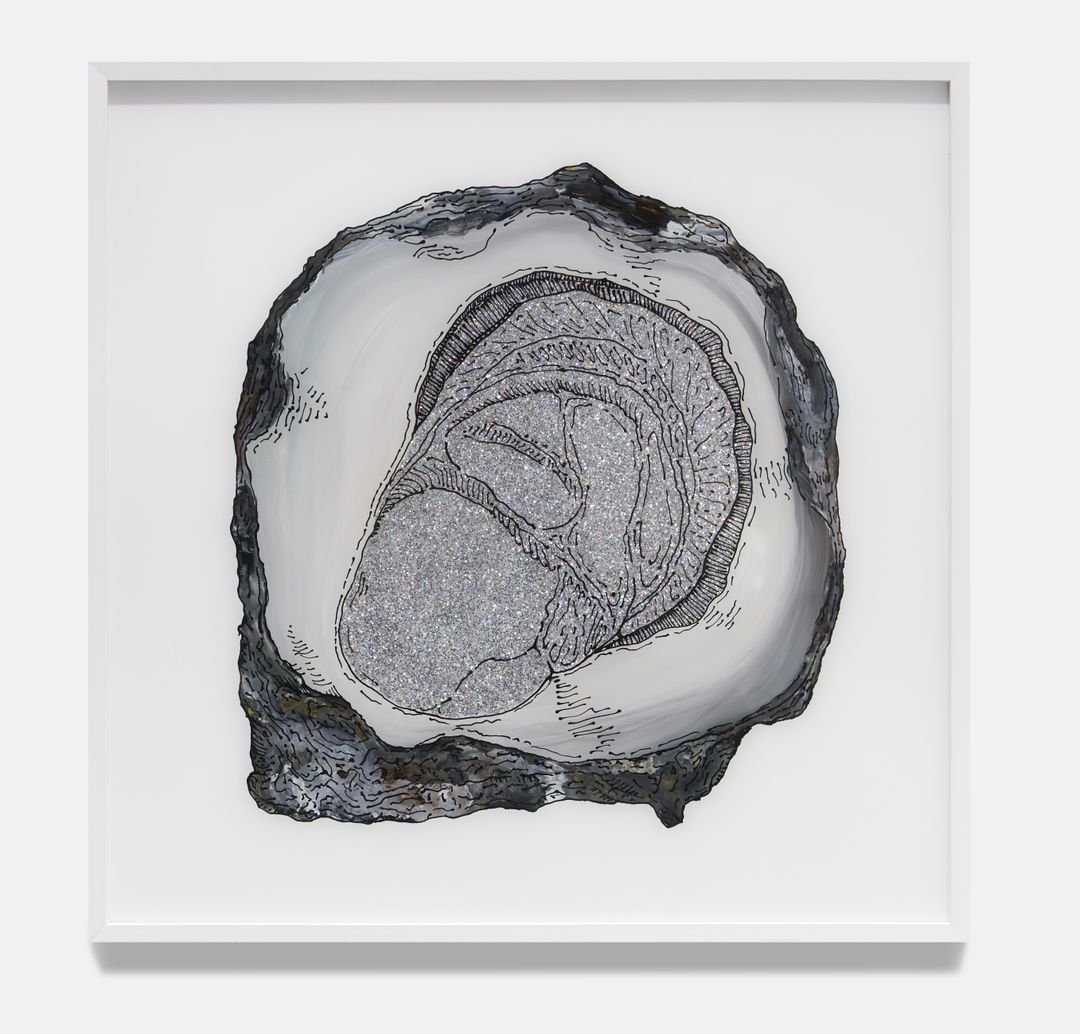

Pamela Harris, Women (Lesbian mothers are everywhere), 1984, screenprint, ink on paper, edition 5/10. Gift of the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art.

As university campuses across the globe once again become sites of placard-waving protest and student sit-ins, Flinders University Art Museum’s exhibition of political posters couldn’t be more timely. Flinders University has deep connections with the history of student activism. Fifty years ago, this campus spawned Adelaide’s Progressive Art Movement (‘PAM’, 1974–1978). The current show at FUMA captures the vibe of this dynamic period in its remarkable collection of historic political posters.

The exhibition curators, art historians Catherine Speck and Jude Adams, have drawn on the museum’s extensive collection of posters to celebrate the legacy of this political group. If you don’t fight … you lose: politics, posters and PAM, is a compelling, tightly focused display of screen-printed posters and ephemera, documenting the activities and political concerns of these seventies art activists. Composed of students and lecturers associated with the Arts and Politics course at Flinders University, the Maoist-influenced organisation, instigated by artist and lecturer Ann Newmarch OAM (1945-2022) and the charismatic Professor Brian Medlin, was committed to harnessing the ferment of the time to achieve social change.

Grouped thematically, the works in If you don’t fight … you lose cogently draw together the preoccupations of PAM members in works by Robin Best, Robert Boynes, Jim Cane, Pamela Harris, Andrew Hill, Ann Newmarch, Mandy Martin, Christine McCarthy, Peter Mumford and the Progressive Printers Alliance. Discrete sections of the installation address US cultural imperialism, representation and gender, workplace conditions, uranium mining and geopolitical issues. A display collates examples of the Eureka flag (reproduced across a variety of PAM items), explaining its potency and meaning; elsewhere art objects made by PAM members gesture towards careers and artistic trajectories beyond the scope of the group’s activities.

Diligently researched, the exhibition’s didactic texts note key background events including university students staging a month-long occupation of the registry Building, industrial unrest at a car manufacturing plant nearby, and protesting against the Art Gallery of South Australia commissioning American minimalist Donald Judd to create a work for the gallery. While there’s no mention of Gough Whitlam’s 1974 reforms that saw the abolishment of student fees making higher education widely accessible, no doubt the influx of a cohort of students previously excluded from university contributed to a sense that change—or even a socialist revolution—was possible. To this end, screen-printed posters, inexpensive to produce and necessarily collaborative, could be widely disseminated as a tool for raising collective consciousness.

Pinned to the wall tightly spaced and unadorned, If you don’t fight … you lose makes a powerful and elegant impression. With few partition walls, the 70-odd posters form a polyvocal cacophony, address the viewer with rhetorical urgency. With such a diverse group of art workers involved, there are a range of techniques and styles. Photographs, either reproduced or as a foundation for illustrations, feature widely. Posters with complex and layered compositions that combine slogans, collaged photographs and illustrations with handwriting and newspaper copy sit alongside simple, more direct examples. An appeal to solidarity and collectivism is reflected in the subjects, for instance in the photograph of marching women that is the basis of International Women’s Day: women march for liberation (1979) by Pamela Harris (1946-1992), or Mandy Martin’s (1952-2021) satirical Collaboration series rendered in illustration, in which a trio of suited men inject a sense of oppression: the suit and cigar, shorthand vocabulary in the propagandist’s toolkit for Very Bad People.

Some of the political references in the posters are lost on the generations who have followed the boomers. For example, Andrew Hill’s documentation of migrant assembly line workers in Adelaide possesses a strangely elegiac quality, as automotive and other manufacturing moved offshore decades ago. Depressingly, many of the injustices, economic disadvantages, and oppression detailed in the posters persist today. The clarity with which PAM drew attention to systemic inequality has an enduring importance, and it’s interesting to note that the issue of social class was paramount.

In Jude Adams and Catherine Speck’s excellent curatorial essay the authors outline how internal disagreements around foregrounding feminism and issues facing women fractured PAM in its later years. What is abundantly clear is that posters by Newmarch and Harris addressing gender, the representation of women in the media and their oppression in patriarchal societies remain eviscerating. Newmarch’s We must risk unlearning and Two versions (both 1975) for instance are richly textural and forceful, as though issuing a corrective to the prevailing culture. Harris’ works Living Doll, Whores no. 1 and Whores no. 2, along with Working Woman and child (all 1981) grapple with issues still affecting women’s lives, economic disadvantage and access to childcare. Regrettably not included in the exhibition, though identified by Julie Ewington in her catalogue essay as the key poster from PAM is Women Hold Up Half the Sky (1978), Newmarch’s ironic interpretation of the Maoist slogan. Two of the most moving posters are by Harris: Adelaide Railway Station 2 (1973) and Women (lesbian mothers are everywhere) (1984) made a decade apart, powerfully affirm women’s lived experience. The strong focus on feminist issues continued through later projects such as the decentred Women’s Art Movement in 1976, which had chapters in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide.

Many will associate political posters of the 1970s and early 1980s with Earthworks Poster Collective at the Tin Sheds Art Workshops at Sydney University who were active in the same period. Characterised by psychedelic colours and pop sensibility the posters from the east coast are generally less strident in tone than their South Australian counterparts. In addition to sharing imperatives and friendships, collaborative cross-pollination occurred between PAM members and feminist artworker Toni Robertson who was a founding member of Earthworks. In 1977, Walls sometimes speak: an exhibition of political posters was key in bringing together posters from across Australia, and touring between the east coast capitals and South Australia.

The substantial catalogue that accompanies If you don’t fight … you lose historicises and amplifies the conditions, circumstances and complex institutional and interpersonal dynamics of that time. Under researched until now, together the publication and exhibition make a significant contribution to art historical scholarship and highlights the work of university galleries: FUMA and the curators have invested in an exhibition that repositions PAM and Adelaide as a significant site of a larger, national story.

If you don’t fight … you lose: politics, posters and PAM

6 May — 5 July 2024

Flinders University Museum of Art

Flinders University I Sturt Road I Bedford Park SA 5042